|

Satya has ceased publication. This website is maintained for informational

purposes only. All contents are copyrighted. Click here to learn about reprinting text or images that appear on this site. |

| November

2006 The Rise of the Global Meat Industry The Satya Interview with Danielle Nierenberg |

|

Courtesy of Worldwatch Institute |

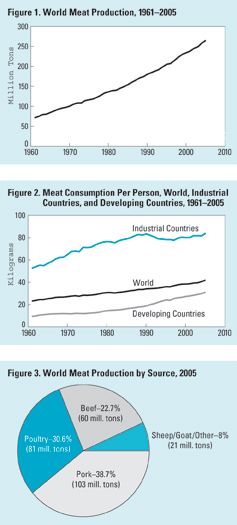

Worldwide, meat production has increased more than fivefold

since 1950, with rates of meat consumption rising fastest in the developing

world

where the

average person consumes nearly 30 kilograms of meat per year. In industrial

countries, meat consumption is still the highest—80 kilograms a

year per person. Danielle Nierenberg, a research associate

at the Worldwatch Institute, has been studying these trends in global

meat consumption. She has traveled

to Asia, Africa and Latin America, and her findings have been published

in Worldwatch Paper 171, “Happier Meals: Rethinking the Global Meat Industry,” and

the Institute’s State of the World and Vital Signs reports. A long-time

vegan, Danielle also promotes sustainable agriculture and works with a local

farmers’ market in Washington, DC.

Danielle Nierenberg shared with Sangamithra

Iyer some thoughts on the

rise of factory farms globally, the outbreak of diseases like avian flu,

and a growing

interest in rethinking our food supply.

Can you give a snapshot of trends in global meat consumption over the last

decade both in industrialized and developing countries?

The short answer is that it has exploded. The biggest startling figure is

that since 1950, meat production has expanded fivefold. Human population

has also

grown, so there are more people to feed. Urbanization continues to grow,

and by next year, for the first time in human history, more people will be

living

in cities than in rural areas. Because of urbanization and growing income,

more people than ever before can afford meat products.

The U.S. and western Europe are the leaders in factory style production.

But, as environmental regulations in some cases have strengthened, and as

animal welfare

has become more of a concern, I feel there is beginning to be a shift in

awareness in how meat is produced and a growing trend toward more sustainable,

humane production.

In the developing world however, where meat production is growing faster

than anywhere else, there is no such awareness. The Cargills, Smithfields

and the

other big players in meat production are taking advantage of this demand

for meat and lack of awareness. They are starting to build their production

and processing

facilities, not only in Mexico, but also in Poland, India, Thailand, the

Philippines and other places, and not get much public opposition.

That is interesting, because as you say here in the U.S., there

is a growing movement for “humanely” raised animal products from

small producers. In the developing world, much of the meat consumed was previously

on a small-scale

subsistence level. How do you reconcile the growth of factory farming in

the developing world, and the slow food movement in industrialized countries

happening

at the same time?

It’s that classic divide between rich and poor. I want to make it clear:

you are in NYC, I’m in Washington DC, so we have a very jaded view of food

production. But in places like Missouri, Iowa, and other parts in the Midwest,

just like in Jakarta and Manila and places in the developing world, factory farms

are seen as this economic boon. They give people jobs and they bring employment

to places where there hasn’t been much growth. I feel like the people who

are interested in food in the U.S. and where it comes from are still a really

select group of individuals, wealthy and well educated for the most part. The

majority of Americans worry about where their next paycheck is coming from. They

just don’t know or don’t have the opportunity or the luxury to

know about these issues.

You mention these factory farms in the developing world are perceived as

economic opportunities, but is that the reality?

No. It makes people serfs on either their own land or land that they don’t

own, but have been using for decades. It is doing the same thing to farmers there

that it’s done to farmers here. In the Delmarva Peninsula, where many of

the chickens in the U.S. are produced, farmers don’t own the chickens,

but get pennies on the dollar for raising them in huge factory farms on their

land. The same example has been set in places like Thailand, where the head of

the biggest chicken producer followed the example of Tyson and did the vertical

integration that has made chicken so “successful” in the U.S.

He owns all the feed and processing facilities and employs a bunch of contract

farmers to raise those chickens for him. It ends up being good for the big

players, and

not for the small or medium size poultry producers, in any of these developing

countries.

And it seems they are wiping those little people out.

Even though these small farms tend to be more efficient both economically

and environmentally, they are still being displaced. The big chicken and

pig companies

are able to come in and monopolize the market. And when avian flu, swine

flu or another disease hits, these big farms—who are often the source of these

diseases—can recover way more quickly than small farms. This is the case

particularly in Thailand. Since avian flu hit, they can clean out their facilities,

import chicks and get into production the next day. It’s very hard

for [small] farmers, and some of them are forced off their land and migrate

to

cities. It is just wiping out a whole generation of farmers and a whole way

of life in

many of these countries.

What are the factors that are moving these factory farms into the developing

world? Who are the big players promoting this sort of meat production?

I’ve found the biggest players unfortunately are the agriculture departments

in some of these countries. They—like our own USDA—are driven by

industry interest. When I visited the Philippines a few years ago, I talked to

agriculture officials within the government, who basically said to me ‘This

is a great thing for our country, to have big farms.’ Whether they

are animals or crops, they see it as a way to spur the economy, create more

jobs,

and do all these things. Some of the other players are big national or multinational

businesses. It looks attractive.

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization has also been a disappointment.

They have built a reputation on saying they encourage and help promote small

farming

in developing countries, and while they have done some great work, since

avian flu has become such a huge problem in Asia, they are now reversing

that policy.

Not only have they recommended that farmers cull their chickens, but one

of their recommendations to control avian flu is essentially reverting to

factory style

production, because they feel this is the best way to prevent avian flu from

spreading. These are disappointments to me. The World Bank and FAO continue

to say they are in support of small farmers and small-scale livestock production,

but whether they are actually helping to promote that remains to be seen.

In your paper “Happier Meals,” it mentions that meat

consumption in the developing world has doubled in the last 10 years. What

can we do to

stop the growth of meat consumption and factory farming worldwide?

[Well] factory farms here are also exporting their products elsewhere. Cargill

has a lot of factory farms in northern Missouri, southern Iowa and all over

the Midwest which are now exporting products to Asia. And because U.S. consumers

really don’t like dark meat in chicken, a lot of the dark meat is often

dumped in Asia, where it is more popular. When you dump any product in a

country you can undersell the national producers. As they are driven out

of business,

factory farms can move in. Stopping it there means stopping it here too.

Here, when people talk about alternatives to factory farming, they

talk about individual food choices and replacing their animal products with

more “sustainable” ones.

Can commercial meat (vs. subsistence) really be sustainable?

I’m a vegan, and I come from a rural town in Missouri. I grew up around

livestock farmers, but became a vegetarian when I was 13. My educational background

is in policy and agricultural development. From a purely agricultural level,

mixed farming—livestock and crops—can be done sustainably. I work

at a farmer’s market here in DC. My farmer friend sells grass-fed livestock,

and whenever I go out to his farm, I can see them grazing very happily on the

land. I know that he uses that manure to grow the fruits he brings to market.

He makes a really good living, but that’s not his only job. Small farmers

in the U.S. usually have to have additional sources of income, but sustainable

livestock production can nourish the land, and you can raise animals humanely.

However in the U.S., we have what Michael Pollan calls our “national eating

disorder.” We eat meat three times a day. It’s cheap. We go to fast

food places. For people to get away from factory style production, we need to

start on our own plates. We just can’t continue to think of meat as

the basis of our meals. Meat in the Middle Ages through the 1800s was a condiment.

It added flavor to meals, and it was considered a luxury. Now we take it

for

granted. That needs to change.

We are at this sort of defining moment, I feel like with Fast Food Nation,

and Michael Pollan’s work, people are beginning to realize the cheapness of

our food doesn’t come without a cost.

I think the critical message is to reduce consumption of animal products,

and encourage small-scale production. But with the growing popularity and

interest

in humane and organic foods, there also seems to be large-scale implementation

of these standards. Can you comment on this?

The organic standards took more than a decade to finally get into place,

and there was a lot of jiggling and lobbying from both the organic producers

and

the meat and dairy industries. I think having standards was a good thing,

and still think for the most part it is. But I know a lot of farmers have

a lot

of trouble adhering to them, not because they aren’t doing things the

right way, but that the standards are sort of rigid, and not very flexible

for small

farmers in particular.

Folks like Horizon and Aurora have twisted and warped the organic standards

to what are essentially organic factory farms that do not treat animals any

better

than the big dairy companies. I find that reprehensible. Horizon and Aurora

have tricked consumers, yet they can still call themselves organic. As organic,

humane,

free-range and whatever other name you put on these products, become more

popular, you are going to have companies that are going to be able to get

around the standards.

And they are going to make a lot of money off tricking people.

So how do we effect change?

We need to not just rethink meat production, but also rethink our entire

relationship with our food supply. How can we treat our national eating disorder?

I have

nieces who are five and six years old who go to McDonald’s three times a week!

As I get older and the more I read about these issues, I think educating kids

about food choices is really important. Eric Schlosser’s new book Chew

on This, directed toward pre-teens, is of vital importance. [We need to] make

agriculture something that people can touch on a daily basis. The growing farmer’s

market movement, the local food movement, those are all signs, but we need

to scale them up massively.

What I don’t want to see is more diseases like avian flu or mad cow disease—a

direct result of inefficient and unsustainable practices like factory farming.

I don’t want bodies to have to fall for people to realize that our

food system is so disordered.

It seems so obvious that all of this is wrong… Why aren’t

small-scale and plant-based agriculture promoted more?

It’s a good question. The people who support that kind of agriculture don’t

have a lot of money or a lot of lobbyists on Capitol Hill or the parliaments

of other nations. There is also a psychological component about feeding people

meat that makes people think that they are well fed. For so many reasons, meat

equals wealth. The whole development community is based on increasing people’s

livelihoods, and what does that mean? Making more money, becoming part of the

middle class and eating “well,” which often means eating meat.

But it’s not natural. As rates of colon cancer, heart disease and obesity

rise, [we realize] we’re not meant to eat that much meat.

There is a growing movement of animal activists working on welfare reform.

Do you think that is curbing factory farming or is it sort of just modifying

it?

Obviously we can’t change everything all at once. All of these small and

big steps are a step in the right direction. I think about this a lot as I work

on this issue and Worldwatch is thinking about putting a book out on factory

farming in the next year and a half or so. What will I say in that book about

the future of livestock production? As I try to look ahead, factory farms are

probably here to stay. I think there is a way to make factory farms less destructive,

more environmentally efficient, more humane, and make the people who work in

them be less abused. It’s not the kind of agriculture I want to see, I

don’t even consider it agriculture, but I still feel they are going

to be around. At the same time, we can improve the economic environment for

small

farmers and encourage new farmers as well.

It seems there are a lot of different areas that activists can devote their

energies to and part of the struggle is figuring out which is most effective.

Is it vegan

outreach, welfare reform, the small farmers movement or is it campaign finance

reform?

It’s all those things. It’s hitting the current system at every level.

It’s consumer awareness, asking your representatives to start looking at

these issues. It’s voting with your fork in any and every way you can,

from going to farmer’s markets to not going to McDonald’s. All those

things are vital. That’s why we have so many nonprofits who can hopefully

take a segment of this issue and do that. It’s also getting into the

schools. Monsanto and other big companies like ADM can provide teaching materials

and

lesson plans in schools. Kids are preached this stuff from the time they

are in elementary school. [We need to breed] the next [generation] of concerned

people who will eat vegan and vegetarian diets.

To learn more and to purchase the report, “Happier Meals: Rethinking the

Global Meat Industry,” visit www.worldwatch.org.