|

|

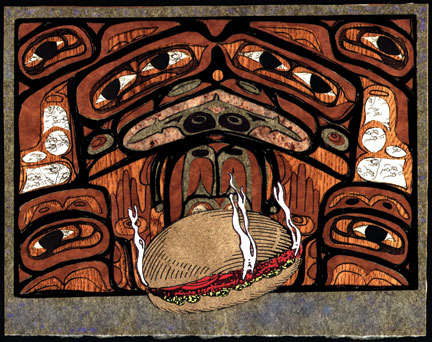

“It

takes six thousand gallons of freshwater to raise 1 pound of

beef.” Image courtesy of Christy Rupp

|

|

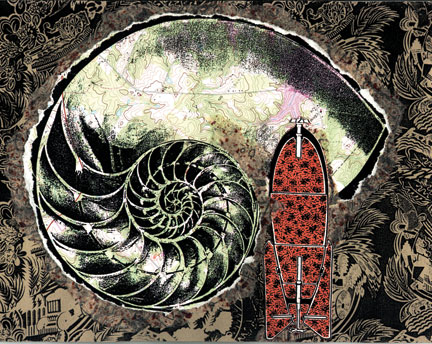

“In

peacetime, the military generates 1 ton of toxic waste per minute.”

Image courtesy of Christy Rupp |

Since the 1970s, New York based artist Christy

Rupp has been creating art that takes a critical look at the social

and environmental impact

of human actions. Her early work—inspired by animal behavior—included

projects on the rodents and roaches we share our cities with. In recent

years, she has been focusing on the commodification and manipulation

of nature, labeling of genetically modified foods, and biopiracy. Issues

around water and toxins also permeate her work. Her Red Tide exhibit

featured turtle sculptures made from the items that destroy their habitat—detergent

bottles. She has also been involved in many public art projects in

cities around the country.

With parody and wit, Christy Rupp recently branded herself as the corporation

Lowgo Global Life Sciences conveying the harms of globalization with the motto “We

make messes.” Sangamithra Iyer had a chance to ask Christy

Rupp about her

art, the single-celled universe, and the links between Roe v. Wade and the Endangered

Species Act.

How would you describe your art and what mediums do you use?

It has been a focus on the intersection of economics and the environment. Materials

have included recycled or green materials, as well as anything that would hold

them together. I am also very interested in off-the-grid, or traditional ways

of working, like gas welding with steel and flame working with glass.

Your work explores the social costs of environmental disruption. Can

you tell

us a bit about this and some of the issues you’ve incorporated into your

art?

I have been interested in making a physical connection to ideas. For instance,

looking at the appearance of toxic molecules, or what a virus looks like. What

do pathogens in tap water look like? Are they [natural] or manufactured in an

effort to sanitize? How does a genetically engineered pesticide really change

the anatomy of insects who selectively evolve tolerance to poison? Mostly I am

trying to understand how humans fit into the cycle, accelerating entropy as we

consume. I am fascinated by the “Terra Nullis” or empty earth viewpoint—that

phenomena are owned by their discoverers, even if those discoverers have no hand

in the creation. It’s also fascinating how much easier it is to destroy

an ecosystem than to control it.

A couple of years ago, I started to read about the effects of globalization,

NAFTA, and the approaching CAFTA accords. I have been trying to make this process

of fragmentation visible by parodizing a corporation, using images and text to

create a phony company.

Could you tell us about your brand Lowgo Global Life Sciences and why you chose

to feature a protozoan on your logo?

Recently I decided to become obsolete as a human, due to racism, greed and war.

Because art is so often regarded as a commodity, it made sense to call myself

a brand, so at least I could continue working. I met with Vivian Verlaan, a young

graphic artist trained in the science of branding, and she helped me come up

with Lowgo. We based it on the exploration of how market forces are affected

or not affected by natural forces. Can greed stand up to Gaia? Is the corporation

really a single-celled organism, which can detach itself from the cycle thereby

enhancing its own wealth? Or is marketing a shabby excuse for a shortsighted

lack of participation in a healthy tomorrow?

You’ve been involved in several public art projects. I was wondering

if

you could explain your Roll Back Bench, and how it links Roe v. Wade and the

Endangered Species Act? Also can you tell us about your work with the Coney Island

Water Pollution Control Plant?

Roll Back Bench was commissioned in 1992 by the University of Washington, Seattle,

as a monument to 20 years of endangered species legislation. At the time, the

Endangered Species Act was before Congress for re-authorization. The bill was

being challenged by anti-environmentalists who had targeted the spotted owl as

a harbinger of economic doom for Northwest lumber interests. By saying that each

spotted owl took away 40,000 jobs, they were framing the debate in much the same

way anti-choice groups equate freedom of choice with murder. The Endangered Species

Act preserves the entire ecosystem, including spotted owl habitats, much the

same way Roe v. Wade preserves a larger context of options, only one of which

is abortion. Both acts were passed in 1972 to protect civil rights, and both

continue to be challenged. The actual sculpture was a cement couch in the shape

of a dam. You can sit in the sculpture and reflect on your position in the debate,

while two large stainless steel salmon try to get by the obstruction you have

become. “Roll-back” is a term referring to the style of couch as

well as a reversion to the past.

“Tidal Filter Fence” is the project designed through the NYC Percent

for Art Program, in collaboration with the Department of Environmental Protection,

at the Coney Island Water Pollution Control Plant. It is a pedestrian and public

access fishing pier at the site of the plant, abutting a wetland, which has now

become a boat basin. The dock-like structure takes its form from the tidal movement

and is colonized by barnacle shaped lighting fixtures, Mussel Benches and a “Catch

My Drift” picnic table. It uses graywater and rain runoff to irrigate beach

grasses surrounding the structure. The idea for the piece is that a healthy wetland

performs the same function as the sewage treatment facility, and it advocates

a greener approach than massive chemical treatment. It has never been constructed

or cancelled, but lingers in denial much the way our development policies are

in denial about the future.

Why is public art important?

Public art is important because it is a voice outside the system. It should raise

questions by making people confront their anxiety and create dialogue.

What are you working on currently?

At the moment I’m interested in the theory of evolution, the way it is

being challenged intellectually and in the domain of public education. I have

decided to recreate some endangered species of birds, constructing them from

hormone and pesticide-laden chicken bones gathered from fast food outlets. This

is inspired by the science of genetic engineering, the idea that we can have

whatever we want by reducing an organism to the sum of its parts, and then reassembling

at will to fit our needs.

What role do you think art plays in activism?

Activism comes from everywhere. Hopefully artists can contribute a sense of visual

richness or ideas, creating new ways to imagine the struggle, and an environment

of inclusivity because so many people are visual, and words can exclude those

who speak different languages or don’t read.

To learn more, visit www.christyrupp.com.

|

|

|

|