March

2007

A

T-Shirt’s Tale

The Satya Interview with Pietra Rivoli

|

|

Nelson and Ruth Reinsch

at their farm in Smyer, Texas.

Photo courtesy of Dwade Reinsch and Colleen Phillips |

|

Pietra Rivoli with Tao Yong Fang, Manager

of the

Shanghai Number 36 Mill. Courtesy of Pietra Rivoli |

|

He Yuan Zhi at her cutting machine at the

Shanghai Brightness Factory. Courtesy of Pietra Rivoli |

|

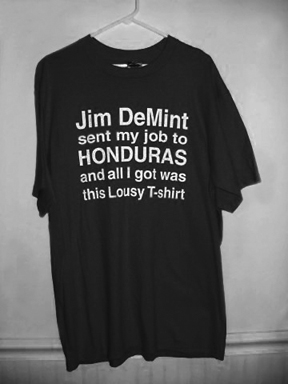

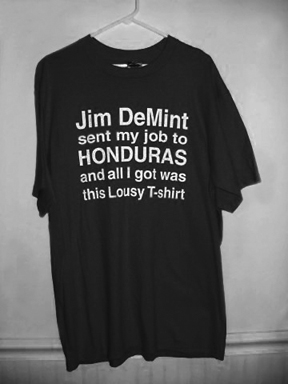

Textile trade issues assume prime importance

in 2004 South Carolina Senate race. Photo courtesy of Tanya Sisk,

South Carolina Democratic Party |

|

A just-opened bale of American used clothing

near the Manzese market. Courtesy of Pietra Rivoli |

In 1999, at a protest at Georgetown

University, a student grabbed the microphone and asked the crowd “Who

made your t-shirt? Was it a child in Vietnam, chained to a sewing machine

without food or water? Or a young girl from India earning 18 cents

per hour and allowed to visit the bathroom only twice daily?” Pietra

Rivoli, a business professor at the university happened to witness

this demonstration. At the time, she did not have the answers to the

protestor’s questions, but over the course of the next several

years, she found them.

Rivoli decided to purchase a t-shirt from the $5.99 bin at a Walgreen’s

drugstore in Ft. Lauderdale, and track its genealogy. What resulted was a book,

The Travels of A T-Shirt in the Global Economy: An Economist Examines

the Markets,

Power and Politics of World Trade (John Wiley and Sons, 2005).

Rivoli takes readers first to the cotton fields of west Texas where the fiber

for her shirt was grown. She explains how the U.S. came to dominate in global

cotton production. From slavery to sharecropping, technology to subsidies, U.S.

farmers gained every advantage. Furthermore, every part of the cotton plant was

turned into profit. The bolls, stems, leaves and dirt mixed with a molasses are

sold as cattle feed to neighboring feedlots. Cottonseed will most likely be bought

by Frito-Lay and end up in potato chips, or sold as aquatic feed to nearby fish

farms.

The next leg of Rivoli’s journey takes her to China where she visits textile

factories and workers, many of whom are young women who have left the farms in

hopes of economic independence. Rivoli explains how the textile industry has

shifted from New England to the Carolinas, to Japan, to Korea and is now largely

dominated by China. Trade agreements have set quotas to restrain China and protect

textile production in the U.S. and other developing nations. Rivoli provides

a fascinating insight into the power and politics negotiating these agreements,

and how our foreign policy can often dictate who the U.S. opens its markets to.

While Rivoli still owns her t-shirt, she also explores its possible fate if it

were donated to charity, where it would be assessed for resale in the U.S. or

more likely shipped and sold to traders in Africa where it would compete on the

market against locally produced apparel. Rivoli hopes her t-shirt conveys that

free markets are not always free, globalization is not a black and white issue,

and the complexity of world trade deserves the attention of both its proponents

and critics.

Sangamithra Iyer had a chance to ask Pietra Rivoli about her t-shirt’s

travels.

What did you hope to learn from this journey? What do you hope people will get

from reading this book?

One of the things Karl Marx said about the effects of capitalism is that we lose

track of where things come from—how they come to be. I think Karl Marx

turned out to be mostly wrong about communism, but had some smart things to say

about capitalism. As markets become more efficient and more global, we get further

away from the things we consume every day to the point we don’t even think

about where they come from. I guess one of the main things that affected me and

I hope affects readers is the idea of stopping every once and awhile and looking

at the cup of coffee in your hand, or the shirt you are wearing and thinking

about where they come from. It’s an important part of being an educated

person in today’s world.

Your book starts off exploring how the U.S. cotton industry reached and has remained

at the top. Subsidies are part of the equation, which amount to more than the

GDP of some developing countries. How do you think cotton subsidies will be addressed

in the 2007 Farm Bill?

Cotton subsidies are gradually going to be chipped away. I don’t have a

precise prediction about which programs can be cut by how much, but I’m

fairly confident that over the next decade, they are going to be eroded and U.S.

farmers are preparing for that.

Moving on to textiles. Can you explain the significance of the Multi-Fiber Agreement,

which put import quotas on textiles from various countries? Can you give an update

on the phase-out of this agreement?

The main impact of the Multi-Fiber Agreement has been to kind of spread the wealth.

Rather than having textile and apparel production being concentrated in two or

three of the most efficient producers, the Multi-Fiber Agreement spread out the

market and gave small pieces to dozens of developing countries. So you had countries

like Jamaica or Mauritius that probably would not have had a textile industry

without the MFA. That was the main effect.

Since the phase-out, it has been kind of interesting. We were only actually quota-free

for about six or seven months of 2005 and the U.S. and European industries were

successful in getting quotas put back on China. These quotas are supposed to

be phased out again, in 2008 for the U.S., and 2007 for Europe. If that actually

happens, we will really see the effect of a quota-free world.

You mentioned that when the U.S. opened markets to Cambodia it was done

with

a contingency of having labor standards monitored by the International Labor

Organization. Does “Made in Cambodia” guarantee sweatshop-free? Why

isn’t all trade mandated with such a requirement?

I think that consumers do have assurances because Cambodia has staked their comparative

advantage on this claim, and so the companies operating there have put quite

a lot of resources into their commitment that their supply chain be pretty clean.

Your second question is pretty tricky. I think it can come close to infringing

on country sovereignty. Countries are free to make and enforce their own laws.

There’s a bit of an imperialistic smell for Americans or anyone else to

say these should be your labor laws. There is also some resistance to the idea

of “Big Brother” telling other countries what ought to be.

I do think you will see more of these things in trade agreements especially with

the Democrats in charge of Congress. China is also under a lot of pressure from

the European and American companies that are producing there, because they just

don’t want to deal with these sorts of problems. Things in China are getting

better, but not as fast as everyone would like and not as transparently given

that they do not have freedom of information. But slowly and bumpily they are

responding.

It is fascinating how the textile industry has played a role in U.S. foreign

policy. You mention the U.S. guaranteeing markets to cooperating countries in

the war on terror. But could this position be used to leverage human rights around

the world?

Generally the way policy works is the State Department focuses on human rights

and tends to be quite liberal in trade. The Department of Labor is more concerned

with labor issues. So the machinations of how policy gets set in Washington are

pretty complicated. What you would need is somebody with a big stake in human

rights who also had leverage on trade. Given that power is distributed in such

funny ways in Washington it is hard to find places where they have both the will

and the way to speak on both of these issues. It’s much more common, as

you know, for them to be responsive to the lobbyists and the business interests.

So it is theoretically possible, but practically not as likely.

In your book you claim the trade in our discarded castoffs to Africa

is the only

leg of the journey where your t-shirt experienced free trade. Interestingly,

you started that section by talking about how women in Tanzania were so striking

with their fabrics, yet you ended up talking about the benefits of trade in American

discards. What does it mean when people are wearing our discarded “Race

for the Cure” t-shirts and can’t afford locally produced textiles?

Karen Hansen, an anthropologist at Northwestern University did a much more exhaustive

study of this. I’m not an anthropologist, I study the economic and business

side, but her observation from field research was that our discarded clothing

was used to contribute to the Africans’ way of dress. Rather than trying

to look like us, you see these women who have combined traditional dress with

Western dress in very creative ways. It is also interesting that the traditional

cloth that many of the women wear is coming from China anyway.

Some of the criticism against this trade is that it suppresses local textile

industries. You suggest it might suppress the domestic market, but not in terms

of exports. I think it is still largely about serving another empire both by

producing cheap clothing for export and having to rely on castoff imports. It

is the developed countries that largely benefit. There might be some marginal

improvements in the lives of people, but that disparity between the rich and

the poor still remains.

Absolutely. Africa is the one region of the world where the disparity is not

narrowing. It is the biggest development challenge that we all face. If you look

at all of the regions in South Asia and East Asia, the income disparities have

been narrowing since the 1970s and Africa is the one place where that is not

true. So you’ll get no criticism from me.

The race to the bottom you talk about seems to be based on the notion that some

people are worth less than others—others with limited opportunities are

exploited for cheap goods we readily discard. While the young woman in the sweatshop

factory prefers this to a life on the farm, she might still be kept in a place

where her upward mobility is capped.

If you look at what’s happened with economic development within the U.S.,

you probably wouldn’t conclude people who worked in factories were capped

in terms of their upward mobility, so why would we say that is true in China?

There is no doubt the biggest barrier to improving the status of life in China

is the totalitarian government in charge and the fact that people don’t

have the freedom to essentially write their own destiny. If you can’t vote,

read or write what you want, then that is a bigger impediment to your progress

as a human being than having a job in a factory. Every time I go back to China,

people are doing better, materially. The women who have worked in textiles have

moved on, either because the textile factories have closed or they got a better

job in the auto factory, but they still can’t vote, read or say what they

want.

If I were concerned of the prospects of the women in China, I would be much more

concerned about that than I would about the fact that they are working in a factory.

What is happening in China now is that the factory workers are holding a lot

of power, because there are extreme labor shortages. The factories producing

textiles cannot find the workers they need to keep producing. The power has shifted.

Rather than having millions of people begging for a job and being exploited,

you have instead thousands of factories begging for workers. I think that is

a sign of progress. China has come a long way. I think it’s quite dangerous

to make judgments about workers in China, without talking to workers in China

because they have much different things to say than those of us who haven’t

been in their position.

As an educator, I hope people on both sides suppress their knee jerk reactions

and appreciate some of these complexities.

I appreciated your effort to tell different sides of the cotton story.

You tell it from an economic perspective, but part of that story that I felt

was missing

was looking at the environmental legacy of cotton. Our highly consumer driven

and disposable society’s demand for cotton might be valued as something

positive in an economic light, but not so much from an environmental perspective.

If I do another edition of this book, the whole environmental story is something

I’d address. Part of that is because I’ve been thinking about it

a lot more, but I’ve also noticed, when I speak about the book this is

something that people are really interested in.

In terms of the conflict between the environment and economics, our goal has

to be to make sure environmental costs are accounted for when we talk about economic

benefits. It is one thing to say this trade is economically beneficial, but if

we haven’t accounted for the environmental cost, then we haven’t

done a complete analysis. We are getting better at being able to quantify and

analyze some of these costs, but in a lot of business and economic analyses,

it is just not a piece of the equation the way it needs to be.

Has your university changed its apparel policies?

Well, they’ve changed quite a bit. Not just my university but also a number

of universities in the U.S. had pretty dramatic shifts in their policies over

the past seven years. We’ve basically gone from knowing nothing about where

our logo apparel came from to knowing almost everything.

We only do business with companies that will disclose their factory locations.

We require all of our companies to have codes of conduct and monitoring systems

largely designed to address labor issues. And there are organizations that serve

the university community like The Fair Labor Association and The Workers Rights

Consortium that did not exist 10 years ago. Both of these are especially important

because they really do the legwork of monitoring factory conditions for us. There

has been an enormous change.

Where will you buy your next t-shirt?

[Laughs.] I’m not going to buy any t-shirts for a very long time. I’m

a bit of an anti-consumer myself. I have enough t-shirts. I have enough everything,

so I’m not actually buying more anything. But I do now pay attention to

where my things come from. If I were looking for something, which I’m not,

I’d be much more comfortable buying from supply chains that I am kind of

familiar with than something from an unknown place.

| |

|

|

| © STEALTH TECHNOLOGIES INC. |

|

|