March

2004

What

Would Henry Do? Pushing the Peanut Forward

The Satya Interview with Henry

Spira, 1995

|

|

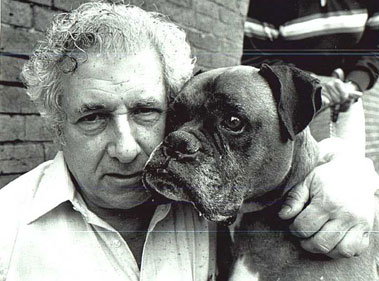

Henry Spira. Photo courtesy Animal Right International |

Henry Spira was the Coordinator of

Animal Rights International. An activist for more than 50 years, he

fought for union democracy in the maritime industry, marched for civil

rights and won major battles to reduce animal suffering. He was instrumental

in persuading Revlon to stop testing cosmetics on animals and convinced

major companies like Procter & Gamble to invest millions in research

for alternatives to animal testing. In the years before he died, Spira

was a lone voice focusing on the suffering of the billions of farm animals.

His work on their behalf included a successful campaign to get the U.S.

Department of Agriculture (USDA) to end its policy of face-branding

steers imported from Mexico. The subject of a documentary and book by

Peter Singer, Ethics into Action: Henry Spira and the Animal Rights

Movement (2000), Spira made a lasting impact on animal advocacy.

The following is a reprint of a two-part interview by Joan Zacharias

originally published in the July and August, 1995 issues of Satya. Henry

Spira died of esophageal cancer on September 12, 1998, at age 71.

What made you become an activist?

While I was growing up I was farmed out to a variety of relatives in

a variety of countries and with a variety of outlooks. This probably

encouraged independence and, later, a willingness to question authority.

I remember my first dream was to liberate all birds from their cages.

Later on, when I was about 12, we lived in Panama and I accompanied

a couple of pistol-packing rent collectors through the slums. I knew

their boss, the landlord, and he lived in palatial affluence and I felt

it was terribly wrong. But at the time, there wasn’t anything

I could do about it.

This was also the period of the Holocaust. There were lots of people

who could do something about that, but they didn’t. They only

expressed the right sentiments—much like our current politically

correct do-nothings.

These sorts of personal and political experiences may well have turned

me into an activist who wants to make a difference where it matters.

And to me, what defines an activist is going beyond the words and sentiments,

turning words into productive action that leads to results.

There are all kinds of injustices in the world. How did you

end up working on animal issues—and why did you select the farm

animal issue?

For most of my life I’ve been active in human rights campaigns,

including the movements for trade union democracy and for civil rights.

Animal rights, for me, was nothing more than a logical extension of

these concerns.

For almost two decades we successfully promoted alternatives to the

use of lab animals. But however you look at this progress, it did not

have an impact on 95 percent of all animal suffering—the nine

billion farm animals raised for dinners every year. A few years ago

we began to plan how we could adapt the earlier strategies to the farm

animal arena.

How do you respond to those people who say, “We’ve

got all these human problems. Don’t you have anything better to

do with your time than worry about animals?”

It defies common sense to make it appear that you’ve got a limited

amount of compassion—that if you use it for animals then you don’t

have it for humans. I think compassion is such that the more you use

it, the more of it you have. Once we start excluding certain living,

feeling beings from the circle of compassion, the easier it becomes

to exclude others as well.

When we see nine billion animals who never had a good day in their entire

lives and we’re the ones responsible for it, that’s when

I think one figures there’s nothing else one can do but fight

in their defense. This does not preclude people from also fighting for

other vulnerable folks. The big difference with nonhuman animals is

that they’re incapable of organizing in their own defense. We’re

the ones who have to do it for them.

Tell us about the work you’re doing on the farm animal

issue.

We’re working on a number of fronts. One of them is the USDA,

which has enormous influence. We’ve established good rapport with

the Department. It takes us seriously and recognizes that we’re

out to solve problems and not just looking for a fight. But the USDA

also knows that we’re capable of conducting a public awareness

campaign, as we did on face-branding. The enormous outpouring of public

concern with the face-branding campaign made it possible for people

at the USDA, many of whom were themselves concerned, to launch a Farm

Animal Well-Being Task Group which is working to upgrade current practices.

Another front is the corporate sector. McDonald’s has declared

that they intend to become a role model for industry in upgrading humane

conditions for farm animals. They’ve created a new corporate position

of Director of Farm Animal Welfare and have contracted with Dr. Temple

Grandin, a leader in designing less stressful systems in animal agriculture.

McDonald’s has also developed a formal plan outlining how they

plan to proceed in this groundbreaking effort. We’re talking with

other major corporations to get them to set standards and also to place

the whole issue of animal well-being on the agenda.

At the same time, we’re also producing generic ads and posters

suggesting that there’s misery in meat, and that for the sake

of your health, the animals’ health and environmental health one

should go meatless or eat less meat. It’s a win-win situation.

We’ve also highlighted the inconsistency of petting some animals

and eating others. And we’re now creating ads that suggest that

eating meat is as harmful to our health as smoking.

Why are these companies suddenly so willing to take measures

to reduce animal suffering?

The fact that McDonald’s set standards for its suppliers was not

necessarily because they suddenly became more sensitive to farm animal

misery. What it became sensitive to is the public’s concern with

this issue. When I talk to any corporate type, the USDA, or whoever,

I just say, “The fact that we’re suggesting something doesn’t

have to concern you at all. It’s just that when we suggest something

where we’re in sync with the public and you’re not, that’s

when you should start worrying.” I don’t think that animal

agriculture today is in sync with what the public wants. But, the public

doesn’t know what’s going on. So, isn’t it our duty

to let the public know? The reason the American Meat Institute put out

humane guidelines a few years ago and that everyone we contacted switched

over from shackling and hoisting [animals] to an upright restrainer

system was because they figured their practices were indefensible in

public debate.

You’ve said that you look to turn walls into stepping

stones of cooperation. But what about when it’s not in someone’s

best interests to cooperate, such as Frank Perdue (CEO of Perdue Farms,

the nation’s fourth largest poultry processor)?

Most of the time rational discussion does succeed. Sometimes people

jerk us around, but you can still see that over the long haul they are

going to be responsive. In the case of Perdue, he didn’t even

think there was a problem, never mind being responsive. But even with

Perdue, it was good strategy to attempt to communicate with him, because

when we launched our public awareness campaign, we could legitimately

say that Perdue forced us into it. And this negative campaign has probably

been very useful in our farm animal initiatives. It reminded those whom

we contacted that while we’d rather engage in productive dialogue,

we were capable of harming their public image.

You’ve been active in many different movements for a long time.

From your own experience, how is change really made?

In our campaign, which focused on research and testing, we

amplified suggestions from the scientific community itself. This helped

create a loop of scientific superstars who agreed that it was time to

reassess traditional practices. After the scientific community heard

the same message from a hundred different sources, it quietly became

part of the mainstream.

You’ve said that you work in an incremental fashion, one

step at a time, and that the further you go, the further in the distance

you can see. Looking far ahead, what do you see?

I see a coming together of the many movements promoting nonviolence

and defending the vulnerable. For too long people have viewed the earth

and everything on it as something to be exploited without limits. Now,

many of us are beginning to recognize that our planet is not just a

quarry to be pillaged and then refilled with garbage. This provides

us with an incentive to promote a practical universal ethic—among

these, that it’s wrong to harm others who, like us, want to avoid

pain and get some pleasure out of life.

It seems to me that common sense suggests that our society will be upgraded

by shifting from greed and macho violence to doing the least harm and

the most good to other humans, to other animals and our fragile environment.

What’s wrong with the all-or-nothing approach? The atrocities

against animals seem to cry out for such an abolitionist approach.

Sometimes this is phrased as, “If humans were vivisected, would

you ask for abolition or bigger cages?”—with the all-or-nothings

presenting themselves as saints while castigating others as sinners.

But remember, the first law of effective activism is: stay in touch

with reality. And the reality is that nine billion non human animals,

not humans, are being raised on farms every year for dinner. For as

long as they remain edibles it is both futile and counterproductive

to engage in the blustering bravado of “Abolition now!”

The animal victims can’t afford this self-righteous, moralistic

stance of all or nothing, because so far it has led to nothing. For

100 years people hollered “Abolish vivisection!” while the

number of animals in laboratories kept skyrocketing. Reduction came

about as a result of campaigns to promote alternatives. If you go for

all-or-nothing, it is a good way to get applause, but it is not a good

way to make progress. I don’t think that the suffering animals

are well-served by the self-indulgence of the politically correct.

Progress is made stepwise, incrementally. You can have ideals, but,

in practical terms, what are you going to do today? What are you going

to do tomorrow? You need a program that makes sense in order to move

ahead.

Critics accuse you of compromising with injustice—“hobnobbing

in the halls with the enemy.” How do you respond?

For us, dialoguing with the other side has produced tangible

results. When you suggest alternatives that are doable and that lead

to progress, and where everybody can come out a winner, then you get

a change that’s a great deal more enduring because it’s

not begrudging.

I think you always need to start off with dialogue, because if you start

off with bashing, it looks like you’re looking to fight and not

to solve problems. The point is to look at issues as problems with solutions,

try to figure out solutions, and move ahead. But, where no action is

forthcoming, we’ve been tough and relentless.

What advice would you give someone who wants to make a difference,

but doesn’t know where to start?

You probably want to select what you’re comfortable doing, be

it big or small. How much time do you have? What resources are available

to you? What are your personal skills, people skills, writing skills?

Do you have a talent for organizing protests or for street theater?

Anything that makes a difference is valid on its own merits. Droplets

turn into streams that can finally turn into tidal waves of change.

You gain confidence by doing. It’s good to be impatient with injustice,

but you need to be patient with yourself. Start off by writing a letter

to the editor, encourage school and company cafeterias to offer more

vegetarian options, ask your library to carry Animal Liberation and

other books dealing with animal protection. Call or write your favorite

media personalities and ask them to tell the “meat is misery”

story.

You’ve been at this for a long time, and the problems

are enormous. What keeps you going? Do you ever get tired of trying?

No matter how big the problems have been, we’ve always been able

to move forward. It’s crucial to have a long-term perspective.

Looking back over the past 20 years, I see progress that we’ve

helped achieve. And when a particular initiative causes much frustration,

I keep looking at the big picture while pushing obstacles out of the

way. And there’s nothing more energizing than making a difference.

I think that to be effective, you must enjoy what you’re doing.

To feel that there’s nothing in the world you’d rather do.

That you find it personally fulfilling and it gives meaning to your

life. It’s a lifestyle where everything is sorted out from the

perspective of “what difference does it make?” Where you’re

not concerned with appearances, popularity, material possessions, social

status and trappings of power. You are concerned with results that will

endure.

Still, it’s been said that we don’t live by politics alone.

Personally, I also get much pleasure from Nina, my playful feline companion.

And I walk in parks and, when I can, hike along the seashore. For me,

being in contact with nature is like recharging one’s batteries.

Do you think you’ve seen a sea change in your lifetime?

I think there’s been a revolution in our attitude toward animal

suffering. It’s totally remarkable that one book, in a couple

of decades, has changed our outlook and even our behavior toward nonhuman

animals. But if there hadn’t been an Animal Liberation

by Peter Singer, then I think the same thing might have happened, just

more slowly. Once all humans are considered within the circle of our

concern, it’s just inevitable and natural that the next expansion

will be toward nonhuman animals.

Are you satisfied with your life?

Yes. Some things I would do differently, but by and large I am comfortable

with what I’m doing with my life. And I enjoy it, too. It’s

exciting, interesting, and I generally feel that I’m doing the

best I can. I think that activism is a lifestyle that more people should

consider.

I think most of us want to be able to look back and figure that, hey,

we’ve done something useful with our lives and, as my current

cliché goes, done more than consume products and generate garbage.

|

|

|

|