March

2004

The

Baader-Meinhof Gang / Red Army Faction

By Richard Huffman

|

|

It wasn’t just about killing Americans and killing

“pigs” (police), at least not at first. It was about attacking

the illegitimate state that these pawns served. It was about scraping

the bucolic soil and exposing the fascist, Nazi-tainted bedrock that

the modern West German state was propped upon. It was about war on the

forces of reaction. It was about Revolution.

The years between 1968 and 1977 represented the most tumultuous era

in West Germany’s internal social-political history. The student

protests of 1968 that had promised so much hope, quickly fizzled into

riots. Many of the leftist students would follow student leader Rudi

Dutschke’s clarion call to gradually change the institutions from

within. But a select few of the radicals had no time for any nebulous

march—they wanted Revolution now, and sought to kickstart the

cause through terrorism. In 1968 Andreas Baader and his girlfriend Gudrun

Ensslin attempted to do just that by firebombing two Frankfurt department

stores—symbols of capitalism.

The Baader-Meinhof Gang didn’t expect to achieve Revolution by

themselves. They assumed their wave of terror would force the state

to respond with brutal, reflexive anger; that the proletarian West Germans

would react in horror as the true nature of their own government was

revealed; and that factory workers, bakers, and miners would rise up

and overthrow their oppressors. They assumed they would be the vanguard

of a joyous Marxist Revolution.

Much of what they assumed about the German state proved true. Light

armored tanks and machine gun-wielding police became common sights on

the streets of Berlin, Hamburg, and Munich. Police would search entire

apartment complexes on the slightest hint of Baader-Meinhof activity.

Random police searches of the vehicles of young, long-haired Germans

became common. It seemed perfectly clear to the members of the Baader-Meinhof

Gang that they had brought to the surface the fascism that had plagued

Germany since 1933—a power structure that had changed little since

the Nazi regime.

For a time, it seemed as if their leftist urban guerrilla warfare might

have a measure of success. Polls showed an extraordinary number of Germans

supported their cause in one way or another: 20 percent of Germans under

the age of 30 expressed “a certain sympathy” for the Baader-Meinhof

Gang; one in ten young northern Germans indicated they would willingly

shelter a member for the night. For the leaders of the Baader-Meinhof

Gang, this was empowering proof that millions of Germans were lining

up behind their cause.

But save for killing a few policemen in shootouts, the Baader-Meinhof

hadn’t really begun their Revolution. There were no decapitated

GIs yet, no maimed press operators. It was therefore easy to support

them; they hadn’t yet truly turned their theory into praxis. This

would all change one year later.

After their weeklong campaign of terror in mid-May of 1972, few Germans

were interested in marching behind the Baader-Meinhof Gang. After the

Heidelberg bomb that shredded U.S. Army Captain Clyde Bonner and his

friend Ronald Woodward into confetti; after that same bomb knocked over

a Coca-Cola machine, crushing another soldier; after the Frankfurt bomb

that sent shards of glass into Lt. Colonel Paul Bloomquist’s neck,

severing his jugular; after the bombs placed in the hated Springer press

offices in Hamburg injured and maimed 17 typesetters and other workers;

after the bomb that almost killed five policemen in Augsburg; after

a car bomb destroyed 60 cars in a Munich parking lot of the federal

police force; after the bomb planted under the seat of Judge Wolfgang

Buddenburg’s Volkswagen exploded, severely injuring his wife;

after all of this terror, the Baader-Meinhof Gang had no support. The

millions of ordinary Germans, whom the faction’s leadership believed

would rise up, never materialized.

Within five days after the bombing spree, they were all in jail. Within

five years they were all dead.

The First Celebrity Terrorists

The Baader-Meinhof Gang were the world’s first celebrity terrorists.

Although they called themselves “The Red Army Faction,”

they were only known in the public’s mind by the last names of

Andreas Baader and Ulrike Meinhof, a popular journalist who had helped

free Baader from prison custody. Coverage of the group was so ubiquitous

that the story index of Der Speigel (Germany’s equivalent of Time

magazine) regularly listed a simple “B-M”—no one needed

the letters explained to them.

They were the true embodiment of the term “radical chic.”

They had style; they set trends. When Andreas Baader was eventually

captured in a nationally televised siege in a Frankfurt neighborhood,

he had the presence of mind to keep his Ray-Bans on as he was being

dragged into a police van, a bullet in his thigh.

The public and the media weren’t interested in the true dynamics

of the membership of the Gang. For most people, the group became a prime

vehicle to project their own assumptions, fears, and ambitions. Nothing

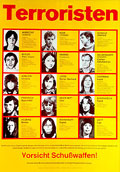

reflected this more than in the late summer of 1971, when seemingly

overnight every bakery window, U-bahn station, kiosk, and lamp pole

became covered with wanted posters, supplied by the BKA, the West German

federal police force, featuring rows of the faces of almost two dozen

young Germans sheepishly confronting them.

The reach of the Baader-Meinhof wanted poster was enormous and unprecedented;

seven million posters were printed and distributed across a country

with only 60 million residents. The photos on the poster were relatively

benign; many clearly came from school photos or from family albums.

But if the photos weren’t particularly menacing, the poster itself

certainly was; its ever-present nature left many Germans fearing that

terrorists were behind every lamppost and phone box. What the authorities

did not anticipate however, was that their poster would communicate

an equally powerful message—unintended, yet devastating in its

allure—to many young German women. Of the 19 faces, almost half

were women.

Radicals?

Rudi Dutschke, a brilliant Berlin student leader, advocated a “long

march through the institutions.” He proposed a decades-long Revolution

by entering the systems of power, working into positions of leadership,

and effecting peaceful, gradual change from within. His arguments held

considerable sway, inspiring many young Germans to begin their own long

marches. Joschke Fisher, Germany’s extraordinarily popular current

Foreign Minister, and so instrumental in the German decision to oppose

the 2003 American war in Iraq, was the most noted of hundreds of former

radicals who deferred their immediate goals and steadily marched into

the upper echelons of the German power structure.

But Meinhof, Ensslin, and their cohort were baldly dismissive of this

approach. Their very first communiqué made this evident: “You

have to make clear that it is…garbage to assert that imperialism…would

allow itself to be infiltrated, to be led around by the nose, to be

overpowered, to be intimidated, to be abolished without a struggle.

Make it clear that the Revolution will not be an Easter Parade, that

the pigs will naturally escalate the means as far as they can go.”

Compared with the coming actions of the Baader-Meinhof Gang, the radical

German student movement of 1968 was “radical” in name only.

The End

Most of the leaders of the Baader-Meinhof Gang were captured in mid-1972.

Their followers would kidnap and kill close to a dozen people over the

next five years in an effort to secure their leaders’ release

from prison, but it was all in vain. The German government had no intention

of releasing them.

The German government used the terrorist crisis to approve new laws

giving them broad powers in combating terrorism. Hard-core leftists

grumbled, but the majority of the German people were firmly on the side

of the government.

After an airplane hijacking by Palestinian comrades failed to secure

the release of the three imprisoned leaders of the Baader-Meinhof Gang,

Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin, and Jan-Carl Raspe all committed suicide

deep in the night of October 17, 1977.

Some would say that the era when West German leftist terrorist action

seemed like a viable vehicle for bringing about revolution ended then.

But the Red Army Faction, founded by Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin,

Ulrike Meinhof, and their comrades, continued right on bombing, maiming,

and killing for almost another 20 years. Finally in April of 1998, the

few remaining RAF members issued a communiqué officially disbanding

the RAF.

For a group whose ideology revolved constantly around self-criticism

and reflection, they were oddly incapable of asking themselves the most

obvious of questions: have we failed? Could we have ever succeeded?

Why hasn’t the proletariat, inspired by their actions, spontaneously

risen up and destroyed those that oppressed them?

Richard Huffman is author of the forthcoming book

The Gun Speaks: The Baader-Meinhof Gang and the West German Decade

of Terror 1968-1977. This is an edited excerpt from Huffman’s

extensive website, www.baader-meinhof.com.

Reprinted with kind permission.

|

|

|

|