|

Satya has

ceased publication. This website is maintained for informational

purposes only. |

To learn more about the upcoming Special Edition of Satya and Call for Submissions, click here. |

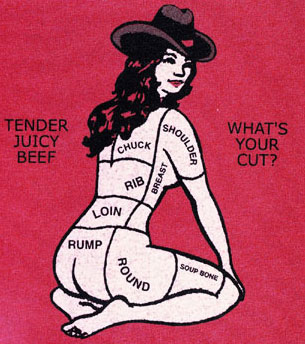

The first chilling moment of awareness I had about the connection between feminism and animal liberation occurred back when I was 15, sitting on the porch with my family about to eat dinner. My dad had barbecued a chicken and it was sitting in the middle of the table. I was looking at it and thinking about the colors, the dark brown and the black. I was thinking it looked burnt, just like burnt skin. I realized that it actually was burnt skin, it wasn’t just resemblance, it was a burnt body. That was when I said, “I’m not eating any dinner, I’m not eating that. I’m gonna be a vegetarian.” That bird, I thought, was conscious once—was once animated with life. Now it was just the centerpiece of a meal. Parts of this once-living bird would even wind up in the trash. In that moment, this collapse—this reduction—became so vivid to me. I think the reduction of “someone to something,” as Carol Adams puts it, is at the core of most violence against other animals. To reduce other animals to things usually means treating their bodies as resources for something you need, manipulating them while they’re alive and/or killing them. I think the way humans are constantly interfering with the bodily autonomy of other animals closely resembles the way males often subordinate females—controlling the body, which is our physical home in the world, our place, and (in a lot of ways) our sense of self. (I guess this is because both forms of domination happen under the umbrella of human-centered “white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy,” to use bell hooks’ analysis.) Control over the bodies of animals and human females is carried out through specific systems of domination such as sexual objectification in popular imagery, abuse in homes, labor exploitation, linguistic stereotyping, and reproductive control. The High-heel Dichotomy But who are “women,” anyway? This question seems to be the—or one of the—primary issues of feminist theory. Definitions that I’m familiar with refer to a set of character and anatomical traits, political conditions, and fashion statements. But popular definitions of who women are don’t allow for much transformation out of, into, or within “womanhood,” so they can feel as painfully restrictive as a pair of high-heels or a tiny skirt that you desperately try to fit into. Not wanting to perpetuate a reductive definition of “women,” I’m just speaking of people with uteruses and ovaries and the various reproductive organs of the female sex. For human females, reproductive control comes in the form of anti-abortion legislation, the financial inaccessibility of contraceptives through health care plans, the scarcity of abortion providers (particularly affordable ones), the illegalization of many contraceptives, “right-to-know” laws, and intimidation from anti-abortionists. According to the Abortion Access Project, 87 percent of all U.S. counties have no abortion provider. Between 1982 and 2003, they report that the number of abortion providers decreased by 37 percent. The majority of U.S. states have parental involvement laws. And over half of all abortion providers were harassed in 2000, and countless more women are intimidated by protesters just for entering a clinic, even for a regular check-up. In the face of all of this, the media, our schools, our families, churches, workplaces and communities instruct females in various contradictory ways about our sexuality, ranging from the mandate to be celibate to the injunction to be accessible sexual objects for males. So many demands: we’re supposed to be sexually available (even objects of rape) but also chaste, we’re denied adequate contraception from our health care plans and yet are supposed to remain unfertilized. These messages vary according to race and class and physical ability and many other factors of identity. I’m a white, financially stable, 20-something female from the South. Still, from what I’ve seen in my life, I’d bet that these contradictory, confusing messages (which feminists often call the “virgin/whore dichotomy”) are familiar (on some level) to most females in this country. African American women seem to be especially frequent subjects of public debate about reproductive control. The debates around welfare reform, for instance, particularly during the time of the 1996 Welfare Reform Act, called up this hostility toward women’s reproduction, especially toward African American pregnancies, which became the imagined national problem in need of a solution. Problematizing African American women’s sexuality is an old patriarchal construct: the hypersexual “black female savage” is out of control and must be restrained, as feminist writers like bell hooks have explained. But history exposes the irony of the stereotype: white male slave owners used enslaved women as “breeders” to produce more slaves. Quoted in an interview, one formerly enslaved woman said she “brought in chillun ev’y twelve mont’s jes lak a cow bringing in a calf.” The Reproduction Farm A few years ago I went to a big conference on reproductive control at Hampshire College. One of the opening speakers, Mina Trudeau, boldly challenged the audience to think about how reproductive control affects other species. For so many cows, chickens, dogs, minks, and other nonhuman animals, the lack of reproductive autonomy is a guaranteed part of existence. Consider farmed pigs. As David Wolfson writes in Beyond the Law: Agribusiness and the Systematic Abuse of Animals Raised for Food Production, “gestating (pregnant) sows and farrowing (birthing) sows are housed in stalls where they are unable to turn around (gestation crates or farrowing crates). Such intensive farming practices result in health problems, including lameness or high death losses” Gestation crates apparently prevent sows from accidentally rolling or stepping on their piglets and make their teats available during lactation. Cows’ reproductive systems are the foundation of the milk industry. Gene Bauston, the founder of a large sanctuary for farmed animals, says: “All cows, whether they live on dry-lot dairy factories in the Southwest or small traditional dairies in the Midwest or Northeast, must give birth in order to begin producing milk. Today, dairy cows are forced to have a calf every year because such a schedule results in maximized milk production and profit. Like human beings, the cow’s gestation period is nine months long, so giving birth every 12 months is physically taxing. The cows’ bodies are further taxed as they are forced to give milk during seven months of their nine-month gestation…it is not uncommon for dairy cows to produce 100 pounds of milk a day—ten times more than they would produce in nature.” According to Bauston, producing so much milk can cause several common physical ailments. One is mastitis, inflammation of the udder. In 1996, about half of dairy cows in the U.S. suffered from mastitis. Dairy cows also develop ketosis, a metabolic disorder, and laminitis, which leads to lameness. Also common are Bovine Leukemia Virus, Bovine Immunodeficiency Virus, and Johne’s disease. Chicken bodies are also captive resources of industrial agriculture. Egg laying hens are subjected to forced molting in factory farming complexes, meaning that light, food and water are withheld for up to 14 days in order to control egg output. This serves to “shock their bodies into another egg-laying cycle,” as Bauston says. Other domesticated animals, like dogs, are also reproductively manipulated. Joan Dunayer in her book Animal Equality points to an article in the American Kennel Club’s magazine that “recommends ‘holding the bitch in the proper position,’ with straps or by her legs, and ‘assist[ing]’ the male in ‘penetration.’” Like farmed and companion animals, lab animals also are bred for mass production. The degradation of these sentient creatures is most evident in lab animal industry catalogues where they are often sold for a price per “unit.” Horses are used to produce the estrogen replacement drug Premarin (named after its source, PREgnant MARes’ urINe). Manufacturing Premarin involves taking the urine from pregnant horses and the mares are routinely impregnated for this purpose. The animal advocacy group United Animal Nations says, “Premarin mares are confined to small stalls for months on end while their urine is collected and…their foals are herded off to slaughter every year to be sold to European meat markets.” Thousands of mares are basically immobilized in these stalls, and in the winter, as one concerned activist explains, “you see ice on the walls [of the barns], and they have to lay down on cold, ice-cold concrete floors.” Constant forced impregnation of these horses is necessary for the production of Premarin. Ironically, Premarin manufacturers exploit the reproductive systems of horses to market their product to menopausal women. The Worn and Weary When reproductive exhaustion has finally worn their bodies down, many animals are killed, especially those in agribusiness. No longer able to produce milk, dairy cows, for example, are killed for meat. Farmers send them to slaughter after they’ve lived only a small fraction of their lives. Sometimes they literally become trash, since their meat is usually “low grade” and used in junk food that often winds up half-eaten in a dumpster. The fight for liberation from reproductive domination isn’t just a human struggle, although many feminists construe it this way. Similarly, if animal liberationists really want to end the oppression of other animals, we’ll have to understand how that oppression is mirrored in the daily experiences of human females. Reproductive autonomy is a need that cuts across species barriers. It is a solid and heavy example of the overall lack of bodily integrity that both human females and other animals endure. Helen Matthews, a.k.a. Homefries, has been working on connecting social justice and animal liberation issues for five years. She has worked with Boston Ecofeminist Action, and facilitates workshops on feminism and animal liberation at conferences, community centers and universities around the country. Check out her online slideshow at www.smartelectronix.com/~marc/rtso.

|