February

2007

Put

to the Test, Vegan is Best

The Satya Interview with Gidon Eshel

|

|

Gidon Eshel and Pamela Martin prepare a salad lunch.

Photo by Lloyd DeGrane

|

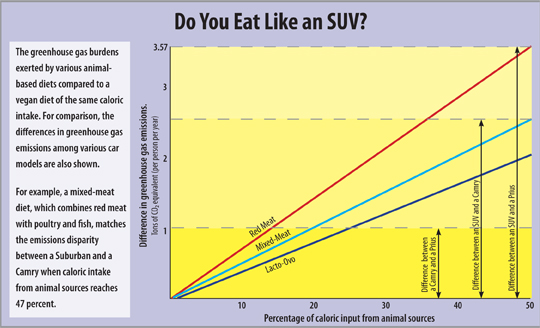

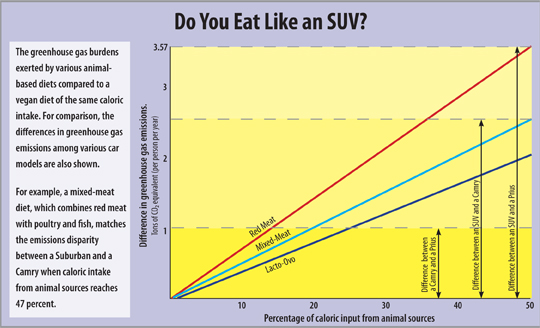

Which causes more greenhouse gas emissions, rearing

cattle or driving cars? This question was posed in a recent report

published by the United

Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, which concluded the livestock

sector “generates more greenhouse gas emissions as measured in

CO2 equivalent—18 percent—than transport.”

Gidon Eshel and Pamela Martin, Assistant Professors at the Department of Geophysical

Sciences at the University of Chicago, have also been making the connections

between food production and environmental problems, comparing individual diet

choices with individual driving choices. Their paper “Diet, Energy and

Global Warming,” published by Earth Interactions last year, examined greenhouse

gas emissions associated with plant- and animal-based diets. Carbon dioxide emissions

associated with burning fossil fuels during food production as well as methane

and nitrous oxide emissions associated with livestock and animal waste were considered.

Their study quantified the greenhouse gas consequences of red meat, fish, poultry,

milk and eggs, and compared those numbers to a vegan diet. They found that switching

from the standard American diet to a plant-based one could result in preventing

an extra ton and half of greenhouse emissions per person per year. By contrast,

switching from a standard sedan like a Toyota Camry to a hybrid Toyota Prius

saves about one ton of CO2 emissions. What you choose to eat could do more to

offset greenhouse gas emissions than what you choose to drive.

Eshel, a physical oceanographer and former cattle farmer, hopes to combine his

research with a civic engagement, recognizing the enormous importance of politics

to societal challenges such as global climate change.

Eshel and Martin plan on continuing their work by setting up a sustainable development

research and teaching center on a 500-acre organic farm in Millerton, NY. There

they hope to quantify the energetic and greenhouse gas consequences of organic

versus conventional, as well as small-scale versus industrial farming.

Before the American Geophysical Union’s annual conference in San Francisco,

Sangamithra Iyer had a chance to ask Gidon Eshel about his work.

Can you tell us a bit about your background? How did you get interested in climate

change research and the social and environmental issues surrounding food?

I’ve sort of combined two parts of my multifaceted pasts. I’m a scientist

now. I used to be a [cattle] farmer [in Israel]. I used to care about [agriculture]

on a daily basis. Now I care about [it] on a global basis.

Pam and I are both interested in environmental problems. At every dinner party

of earth scientists, there’s always a discussion about [the impact of food

production on the environment], but nobody quantifies them because everyone is

busy doing whatever it is they are doing. So Pam and I just did it, we quantified

[greenhouse gas emissions linked to diet] to the best of our abilities.

So what do they serve at the dinner parties of earth scientists?

[Laughs.] It is pretty much the usual fare. But Pam and I are mostly vegan. I

probably derive 99 percent of my calories from plants.

When did you make that transition?

Twenty-five years ago. I’m 48.

When did you leave the beef cattle farm?

Around that same time. Jewish Israelis didn’t really eat fresh meat—it’s

too expensive and the competition from Argentinean and Brazilian frozen meat

was too fierce. So I sold 100 percent of my beef to Palestinians. I loaded my

cattle on trucks to Gaza, which was four hours away from where my cows were grazing.

I only got paid after they were slaughtered. So I would actually go with my friends,

the cows, to see their demise and [make sure] the slaughterhouse was not cheating

me by rendering the meat less desirable than it was.

I would spend days on end in slaughterhouses. You have cows walking down the

chute and coming out the other end as meat. It happens unbelievably fast. To

take a large, clearly thoughtful animal like a pig or cow and kill it is pretty

horrible. That is basically when I stopped eating [meat]—I haven’t

eaten any kind of ruminant or land dwelling mammal since then.

Much of your work is about how our dietary choices have geophysical consequences.

Can you talk about what this means?

It is a broad topic, but you can kind of put it in perspective by saying each

one of us is a very small user of the planetary supply system. The planet has

a certain amount of land, water, sunshine...etc. It has a certain set of physical

limitations. Everything we do exerts some pressure on that system and food is

not trivial.

We talk a lot about the effects our driving choices have. Those are very important,

but there are other things just as or more important. One of which is dietary

choice.

Which brings us to your recent “claim to fame”—your

study of the impacts of meat vs. vegan diets on global warming. Can you describe

this

study?

It is one of those things that a million people thought about. On the topic of

our relationship with the planet, you have a huge oversupply of opinion, and

precious few facts on which those opinions are based.

The study asks several questions, but the main one is: Given that food consumption

exerts some pressure on the planetary system, and given the average American

is responsible for the emissions of about four tons of CO2 equivalent per year,

and given how much more efficient plant-based foods are compared to animal-based

foods, what’s the difference [between] various dietary choices? Our yardstick

was the completely plant-based diet. That was considered zero in our calculations

and everything we quantified was the added emissions for which a person is responsible

above and beyond what a vegan person is responsible for, if he/she chooses to

obtain some fraction of their calories from animal sources.

|

Graph courtesy of Gidon Eshel and Pamela Martin |

And the result?

The bottom line is if you eat the mean American diet, then you are

responsible for the emissions of an extra ton and a half of CO2 equivalent

per person per

year, as compared to a vegan who eats the same number of calories but derived

only from plants.

Does it take into consideration the distance traveled for food?

It does implicitly, but not explicitly. We tally all the inputs to the food

system including transportation. But that question can be asked differently.

What’s

better, a big bowl of salad for dinner, but all of the ingredients are from California

or Mexico or to have pork chops, but the pigs were raised less than 200 miles

away? That is a really complicated question, which we didn’t answer. We

just said, given the current structure of the food system, where people do generally

feel that they can’t [go without] lettuce no matter what season it is and

given there is a lot of transportation expenditure built in, what is the difference

between a vegan diet and any other diet?

But if we all subscribe to the notion that our diets do matter a great deal

to the planetary system, then we also agree that we must modify them. We are

in

a position to [ask], how do we modify them? Do we grow local? Do we go organic?

Do we go vegan? All of those things have important environmental consequences.

They are ethical questions as well.

Your work shows that a diet consisting of plant-based foods is healthier

for

the planet. There is a growing interest in more sustainable animal agriculture.

From an environmental perspective how does a vegan diet compare with, say, “grass-fed” beef?

Actually grass-fed beef is not really all that benign. There is a paper that

shows they emit four times as much methane per day as their “colleagues” in

the feedlots. Methane is about 20 to 30 times more potent molecule per molecule

than carbon dioxide.

There is definitely room for grass-fed beef in the marginal lands of the west

where nothing else probably can be grown and where biodiversity or endangered

species are not compromised by grazing, but a very small portion of all land

used for grazing satisfies those conditions.

What has the response been to your study from both the scientific community and

general public?

Extremely enthusiastic from both communities. The paper has been intensely

downloaded by scientists. It’s too early to say how much it will be cited because

that takes a couple of years to kick in.

The public is mostly supportive, sometimes dismissive. Let’s face it, our

findings compare many things to being vegan, but what portion of the population

is vegan?

Our study provides a tool to quantify the emissions consequences of obtaining

some percentage of your diet from animal products. It needs to be augmented

with a lot more work.

How do you hope to connect your scientific research with public policy? They

are re-writing the farm bill this year.

Yeah. I have exactly zero hope for that. But if I had my way, I would say there

is no question the basic infrastructure of American food production is very

broken. It is a huge waste to devote and sacrifice almost the entire Midwest—the

most fertile and perfectly suited ground for agricultural production—to

soy and corn interspersed with intense feeding operations. That is extremely

inefficient and imprudent.

There are other things we are going to be constrained by sooner or later, like

water. Given the intensity of production, the big aquifers underneath those

areas are declining. And that is definitely a major reason for alarm.

Hopefully our tolerance to rendering large swaths of land toxic in a very serious

way by application of herbicides and pesticides is being reduced. One reason

we need so much of those is because of monocultures. But if there is more diversity

on the land, there is more of a balance between predator and prey in the insect

kingdom, and less need for those chemicals. Herbicides and pesticides require

a lot of energy for their production, and energy is almost free in this country—artificially.

How much influence does the scientific community have, say in the farm bill?

I would say zero—especially scientists like myself who worry about environmental

consequences. They probably listen a little bit to people from Cornell or Iowa

State, or University of Illinois, who tell them things specifically about current

practices and what can possibly be done to inch up production a little bit.

These guys are also part of this whole infrastructure, which is based on the

notion that corn, soy and a little bit of wheat is what the Midwest and the

eastern Great Plains were designed for by divine fiat. That is not the right

kind of

thinking. What we need to be thinking about is what these places are optimally

used for in reality.

In terms of public dialogue about climate change, like in the movie

An Inconvenient

Truth, it doesn’t seem like they are making those links to animal agriculture.

Do you find that to be the case?

Yes. Well An Inconvenient Truth, if I’m not mistaken, doesn’t have

any mention of that. Which is fine. I think it is a wonderful movie and was really

impressed with it, and I am even more impressed with the public role that Gore

took after he was no longer the president-elect. I think he is perfectly aware

of the many aspects of the problem that were left out of the film. He knows a

lot, but he’s also a very savvy seasoned politician. In order to maximize

your punch you need to pick some things and not dilute the message too much.

But the film ends with things you can do in your daily life… switch your

light bulbs, buy a hybrid… It doesn’t say eat less meat.

Yeah I agree, in that he could have thrown us a bone. Pun intended. Agricultural

issues in general, and veganism in particular, do squarely belong there.

To read their paper go to http://geosci.uchicago.edu/~gidon/papers/nutri/nutri.html.

| |

|

|

| © STEALTH TECHNOLOGIES INC. |

|

|