February

2007

Editorial:

A Troubling Ambivalence

By Sangamithra Iyer

|

|

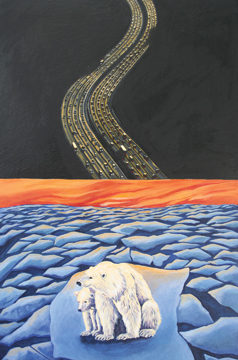

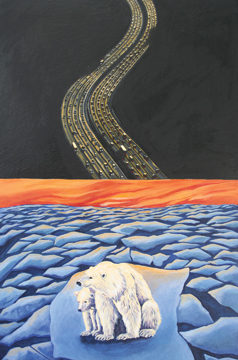

Rushing to Oblivion.

Original

artwork by Michelle Waters |

During the arguments of a Supreme Court case on whether

the Environmental Protection Agency should regulate greenhouse gas

emissions as pollutants,

Justice Antonin Scalia blurted out: “Troposphere, whatever. I

told you before I’m not a scientist, that’s why I don’t

want to have to deal with global warming, to tell you the truth.”

Polar bears, the Inuit and other Arctic inhabitants probably don’t want

to be dealing with global warming either. Unfortunately, they can’t dismiss

it that easily. The permafrost is melting and ice caps are receding, as houses

sink and polar bears drown in search of food.

Across the globe, Omar al-Bashir, the president of Sudan, denies reports of genocide

in the western region of the country, Darfur, even as the violence escalates

and spreads across borders into neighboring Chad and Central African Republic.

Over the past few years, Rahama Deffallah of the Darfur People’s Association

of New York has lost 47 members of his family in the genocide. His 90 year-old

parents have fled their village and are seeking refuge in a cave. While it is

painful and hard to come to grips with, Rahama simply can’t ignore what

is happening in his homeland.

If you scan the news, it’s hard not to be bombarded with all the ways humans—with

our direct action or inaction—are contributing to the extermination of

all kinds of life. Even with that awareness, what’s most troubling is our

response—it fails to commensurate with the magnitude of the problem.

Business As Usual

In reading Elizabeth Kolbert’s Field Notes from a Catastrophe (Bloomsbury,

2006), I became familiar with some of the lingo climate scientists use. For example,

dangerous anthropogenic interference (DAI) is used to describe the point when

a catastrophe due to human activities becomes unavoidable. Scientists are trying

to predict what level of greenhouse gas concentration will be our threshold.

And in predicting when we’ll reach our DAI tipping point, they figure in

the effects of BAU, business as usual—their euphemistic expression for

our vastly consumptive and destructive lifestyles.

A recent UN Food and Agriculture Organization report, “Livestock’s

Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options,” assesses the impact meat

production has on the planet, in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, land degradation,

water usage and pollution. While the report concludes a destructive legacy and

notes that global meat and milk production is expected to double by 2050, nowhere

in the recommendations do they suggest a reduction in, let alone elimination

of, meat consumption.

In relation, a recent paper in Science warned that if current trends continue,

the world’s fish supply may run out by 2048 due to overfishing and environmental

pollution. Rather than removing aquatic critters from our plates, most environmental

publications and groups suggest using “sustainable seafood guides,” to

counter this problem. Grist columnist Umbra Fisk defended her fishy advice by

saying, “No one wants to join a No Fun Club, and no one wants to read Umbra

Says No Again on a twice-weekly basis.” But what’s at stake here

is far greater than the quality of her column. A reluctance to stray too far

from “business as usual” is what’s causing dangerous anthropogenic

interference.

With regard to mass extermination of fellow humans, it’s been almost 60

years since the UN adopted the Genocide Convention, but all we have to show for

it is too little, too late or nothing at all. If you look closely, business as

usual is also at play. In the case of Darfur, you have China protecting oil interests

in Sudan, Egypt protecting its water source, the U.S. hoping to glean terror

intelligence from the regime in Khartoum, and Russia profiting in the arms trade—literally

supplying weapons of mass destruction. In this case, business as usual has led

to dangerous anthropogenic non-interference.

Genocide and Ecocide

Kolbert concludes her book by stating, “It may seem impossible to imagine

that a technologically advanced society could choose, in essence, to destroy

itself, but that is what we are now in the process of doing.”

I’ve been pondering this while looking at our collective response to global

warming and genocide. In both cases, there is often dancing around rhetoric.

Is it “genocide” or “acts of genocide”? Is it “global

warming” or “climate change”? Skeptics dismiss both as “natural,” claiming

human conflict and periods of warming are part of our history. But the rate and

scale at which these acts are happening are hardly natural, putting responsibility

squarely on our shoulders.

The U.S. and China play significant roles in addressing both of these problems.

But if our governments do not step up to plate, the people must. Still, a military

solution, humanitarian aid or a magical technological fix isn’t going to

save anybody if we don’t address the root of our problems—business

as usual.

The Uselessness of Hopelessness

I recently heard Philip Gourevitch, author of We Wish to Inform You that

Tomorrow

We Will be Killed with Our Families, talk about reporting on the genocide in

Rwanda. He offered much criticism and analyses of the world standing idly by

as one million people were killed in 100 days. However, he offered a “troubled

ambivalence” about the role of intervention. Even amongst do-gooders, it’s

unclear whether we know what or how to do the good thing. Are we able to fix

it or do we become part of the problem?

While I understood and related to his reservations, I felt a little nauseated

listening to this discussion in the comfort of a public space in Brooklyn, while

others across the globe were being slaughtered.

I had a similar experience listening to a climate scientist from NASA’s

Goddard Institute for Space Studies discuss what to do about global warming.

He said it might be too late to change it. We should have started asking this

question decades ago. “Essentially we’re screwed,” he concluded.

While it’s hard to know what to do with this information, it is even more

frustrating to not do anything. Inaction due to ignorance or apathy is infuriating.

Inaction due to despair is futile. Yes, we’re screwed, but some of us are

more screwed than others and some of us screwed up more than others. There’s

a whole lot of justice and injustice to address. Maybe it’s time for atonement.

Maybe it’s time for revolution. Maybe it’s time we realize we are

talking about the death of the planet and start valuing life on earth…because

it will all be gone soon if we continue business as usual.

A troubling ambivalence is a luxury none of us can afford.

| |

|

|

| © STEALTH TECHNOLOGIES INC. |

|

|